An olive harvest: Plant description

1. Domenica

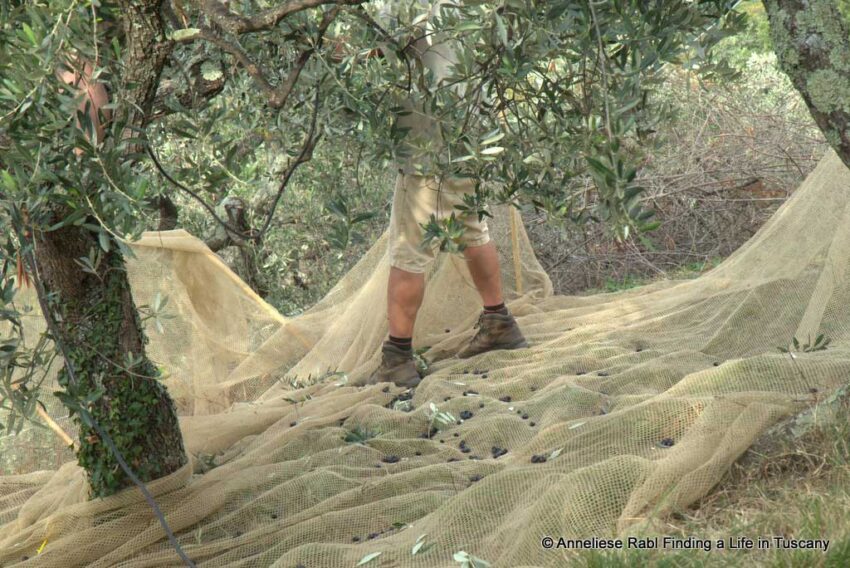

Early in November is usually the beginning of the olive crop season and if it does not rain, we shall start harvesting today. It is cold but dry and I arrive punctually at my new workplace, the olive grove known as campo (field). Three men are already working. On well-fixed ladders, tied around the strong upper branches of the trees. They are picking the olives by hand and make them fall into the nets placed under the trees. It is the women who gather them – among them me – and the children.

We also draw the nets to heap the olives – unfortunately also the leaves – and separate one from the other. The sorting is boring but important and must be well learned. Too many leaves make the oil bitter and can affect the smooth process in the oil mill. They are also partly responsible for the typical, green colour, which many people greatly appreciate. The olives are then transferred to boxes.

We have just finished gathering the olives from the first tree when a strong wind rises and brings deep, black clouds. Continuing the harvest could be dangerous, because skilled pickers know that olive branches simply break without giving any forewarning. As we do not want to lose the whole day, the men decide to place most of the nets under the trees. These must be fixed very well to avoid the wind blowing them away. Before doing this they ask me to gather the olives which have fallen on the ground. Indeed a backbreaking job and hard on the legs, but nevertheless important. This is at least this is what they tell me, and in the end it has to be done.

The grove is slightly inclined. Therefore, one of the first things to learn is gathering the olives in a kneeling position bent towards the slope. Definitely not the other way around to avoid suffering of the knees. These little drupes are really tiny! Incredible, how perfectly they hide in the grass, under the leaves and between the damp clods of earth…

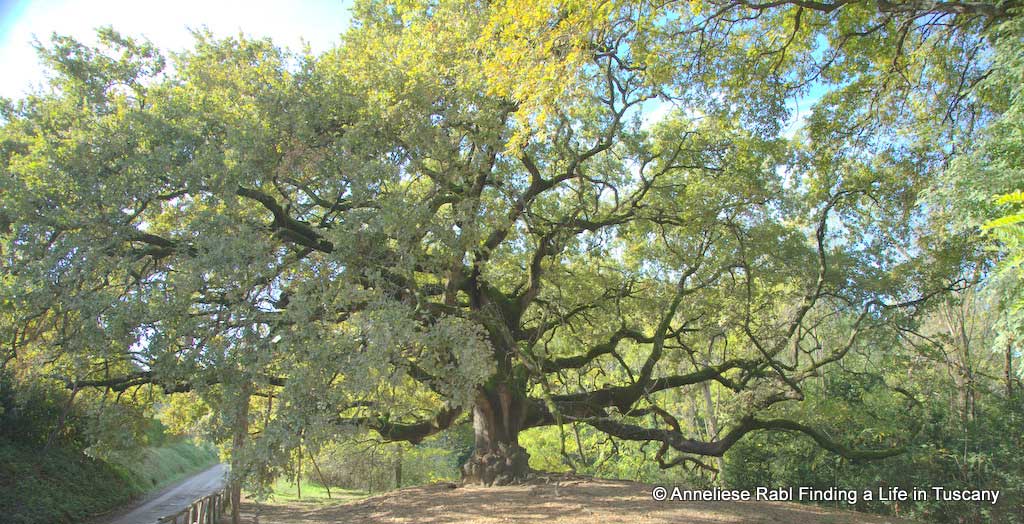

I have a closer look at the olive trees around me. It would not be a bad idea to find out more about these companions of the following Sundays. The problem is that I have no relationship at all with the Olea europea sativa, its name in Latin. There is no resemblance to the trees of my childhood. It is not huge like a fir, its branches do not invite the building of a tree house. It doesn’t have the strong, confidence inspiring trunk of an oak either. The leaves do not have a pleasant smell. The flowers are tiny, of an insignificant white/greenish colour. With its drupes, finally, you cannot create small figures or animals as you can with chestnuts or acorns.

These memories do not make the tree more likeable to me, but I try not to be prejudiced. The olive trees around me are of average height. Usually they do not pass three, four, rarely five metres, although I have seen some reaching twelve metres and more. The olive tree owners keep the trees short by pruning them regularly to facilitate harvesting. This is more than comprehensible because the fragile branches do not actually invite you to climb up high among the clouds.

The olive tree is an evergreen. If I were pedantic I would have to specify that it is not really green. The definition does not refer to the colour of the leaves but to the fact that it never remains without leaves. By the way, they are grey green on the upper side, silvery underneath and covered with fine down. The latter, in fact, prevents them from drying up. The little, thin, longish-oval leaves feel indeed smooth when touching the upper side.

“Are you sleeping?” I hear a voice behind me. One of the pickers on a nearby olive tree laughs.

“No”, I answer “I just wanted to have a better look at the leaves”.

“Do you know why the olive tree doesn’t grow in cold countries?”

“Why don’t you tell me?” , I ask him, smiling.

“Well, it needs the right temperature to grow well. During gemmation, it must not fall under ten degrees centigrade. In this case you can admire the long, luxuriant clusters of small white-greenish flowers around May/June. In summer, when the drupes start to grow, the tree needs a temperature of at least fifteen degrees centigrade. In any case not less than twenty during ripening, i.e. when the colour of the olives changes from green to yellow and finally to purple. Fifteen degrees centigrade is the temperature required for perfect ripeness, around October/November. In fact, as you see, we are here to harvest them.

Olive trees can even tolerate temperatures of five degrees centigrade below zero, which are sometimes reached during the harvest season. This is because they are not really sensitive to cold, but to sudden temperature variations, responsible for crevices in stems and branches. Olive trees grow well on arid soil and need little water, however they love the delicate spring and summer rain. This specific need for certain temperatures is the reason why all attempts to extend their cultivation towards northern and rougher regions have failed. In a few words, your country is too cold and too rainy.”

“Thank you! That was indeed very interesting”.

“You are welcome. You see, the Mediterranean people have a very special relationship with the tree, that you northerners cannot understand”, he continues with a proud smile on his face. “For us it is a symbol of wisdom, beauty and peace. Olive trees and water give us all we need. Shadow in summer, firewood in winter, nutritious fruits, oil for cooking and for lighting. This might not be very realistic, (in fact, it isn’t!) but gives the idea.

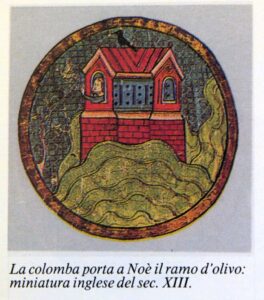

What about the importance of the olive tree in the Universal deluge?! After endless days of rain Noah let a dove fly to see if the water had started to go down and land could be found. On its first attempt the bird did not find earth on which to land but on the second it returned in the evening carrying an olive branch to signal the end of the Universal deluge. When you next go to Florence, take some time to visit the cloisters of Santa Maria Novella and look at the fresco “Universal deluge” by Paolo Uccello (1397-1475). He painted this marvellous scene in his work of art.”

“I’ll do that.”

The ice is broken. Someone else explains that there are several varieties of olives, subdivided in three groups. There are olives to produce olive oil, those to be eaten at table and olives for either use. The different shapes and properties of the olive or drupe, the correct botanical term, differ quite a lot from one variety to another. However it always consists in skin (exocarp), pulp (mesocarp) and woody stone (endocarp), containing the seed. The oil inside the drupe develops while the olive is ripening. It contains the largest quantity of oil when the drupe shows its most intensive colour, i.e. a little before it is completely ripe. This is the moment when the oil content of the pulp reaches up to seventy percent oil and the stone the remaining thirty percent.

Before the drupes reach this grade of ripeness they do not contain any oil, but a mixture of organic acids and sugar. When the olives are ready to be picked they contain about 50 % water, 20-24 % oil, 20 % sugar, 6 % cellulose, 1,5 % proteins. The grade of ripeness during harvest is decisive for the organoleptic properties of the oil. Also important is the harvest process and transport. Last but not least the time that passes between picking and pressing the olives determines the final quality. Generally you could say that the table olives are bigger than those for the oil production. They also have a larger proportion pulp/stone.

The main qualities of the other olives consist in a better yield and a higher quality of oil. Here in the campo we are gathering the qualities Frantoio, Leccino, Moraiolo and Pendolino, species cultivated in Tuscany by tradition for centuries. In our case – we are not official producers – they are being used for the oil production as well as for the home made preservation in brine by simply picking the same perfect olives (in spite of my previous words).

Our first working Sunday is drawing to an end. The weather is rapidly getting worse, the sky is becoming darker and darker. There is a strong wind and the clouds are racing over our heads with impressive speed. My feet are getting cold, my hands too, mainly the fingertips. It is time to go home. During this first harvest day I had noticed a slight backache. After hours and hours in the same position it was not easy to return from a bent to an upright one.

When I arrive home I realize that my legs are numb and not even a long, hot shower helps to make them feel better. Meanwhile, however, it has become clear why those people to whom I had talked about my intention to take part in picking olives had all looked at me with compassion. And I also understand why almost all the members of the owner’s family had something to do elsewhere this Sunday.

Why did I have a good time anyway and what, despite all, made me feel so happy and satisfied? Could it be the contact with these genuine, openhearted, quick-witted Latinos with their sharp and ironic remarks, so different from the taciturn, reflective, melancholic people from my country? These thoughts remind me of my roots: what am I doing in an olive grove? Where are the fir and oak trees of my fatherland??

Leave a Reply